The traditional use of personas in UX can help us describe and communicate generalisations about our users at a particular point of time. But often they are limited by focusing in on a stage of a journey rather than the journey overall. The context in which a decision is made will shape the reaction of the users as much, if not more, than the basic persona type of the individual.

Dynamic personas expand the scope to allow us to maximise interactions, products and services for real people, living real lives.

What is the issue with traditional personas?

My view on personas has changed over the years. They were essential when I first started out in UX but, as time went on, they became expected. Fast forward a little bit and, to me, they started to feel like a hinderance. Personas are useful tools for storytelling and encouraging empathy/buy-in from stakeholders; but they are too fixed to really represent reality and to feel useful for me as a designer. Even with the principle of revisiting and revising over time, any one iteration of a persona remains too rigid for it to be an effective representation of a real person. Waking up on the wrong side of the bed can entirely alter how a person will react from one day to the next. So, what to do?

The real issue is that for personas to be effective they can’t be so static. There are many factors that will impact how a person will respond in any given situation outside of basic demographics. It isn’t enough to just understand the user, we also need to understand the decision being made:

- What is the context of the situation/action? Is it one of leisure or necessity?

- Is the type of decision that is required inherently emotional or rational?

- What level of expertise does the user have in the area that this action is occurring?

- Is there clear intent from the user? Do they have a clear idea of what they want?

- What level of conviction does the user have? Will they require a perfect solution?

This logic applies whether we’re talking about what restaurant to visit, bank account to open, phone to buy or software to use. So if we’re attempting to create personas to assist us in creating digital experiences (or physical ones), we need to embrace the idea that real life means that any person’s behaviours will change, become unpredictable, break down, when faced with a different cocktail of those factors listed above.

The need for change

While creating a mobile application for a large healthcare/insurance provider a few years ago, we first set about conducting a thorough discovery phase. This included interviewing users from around the world to understand their wants, needs, concerns and ways of life. Personas were an essential deliverable as part of this phase of the project, but it was clear that the traditional persona format wouldn’t work. In fact, no number of revisions over time could make it work. The problem is, taking myself as an example, although in everyday life I could reasonably be described as confident, outgoing, headstrong (to a fault, perhaps) and so on; as soon as health issues are on the cards, those traits disintegrate immediately. Similarly, if I am profiled as the user, but the journey being traversed affects my child, my mindset is different again.

In the real world, the situation and context of the need has so much sway over my behaviours that any chronicling of my usual personality traits, needs and pain points becomes largely irrelevant. Our research ultimately supported this notion: Confident at home, nervous while away. Laissez-faire about a health issue of their own, distraught when it was their child. The list of examples stretches on and on.

So, in this project, I cobbled together a solution that detailed a range of situational variables that needed to first be defined to understand how a user would respond in different settings and while making different decisions. I had inadvertently created dynamic personas.

What became clear throughout this process is that we need to think about how we design for situations just as much as for individuals.

The importance of decisions

Let us look at another example of where dynamic personas are vastly more effective, the world of finances. If you take a classic example of a persona that you may have seen over the course of the last 10 years, we may know basic information about them such as: Female, 35 years old, mother, high technical literacy, uses an iPhone, low level understanding of banking and ‘looking for a savings account for her child’.

This information is useful as it can point toward a range of products or services that the user may be interested in. But, if you want to know how to assist, convert, target and optimise that experience/journey to arrive at a mutually beneficial outcome for the user and business alike, you must understand the full dynamic context of the situation.

Let’s think a bit more deeply about the decision this user is making:

- Context: There is a necessity to make a decision. She is not doing this for fun

- Type: A rational decision must be made, not an impulsive one

- Expertise: The user has a basic understanding of things like interest rates, but not much beyond that

- Intent: Goal oriented. The user just ‘needs to get it sorted’

- Conviction: Satisficer approach. The user knows to avoid a bad interest rate but is happy to settle on other aspects

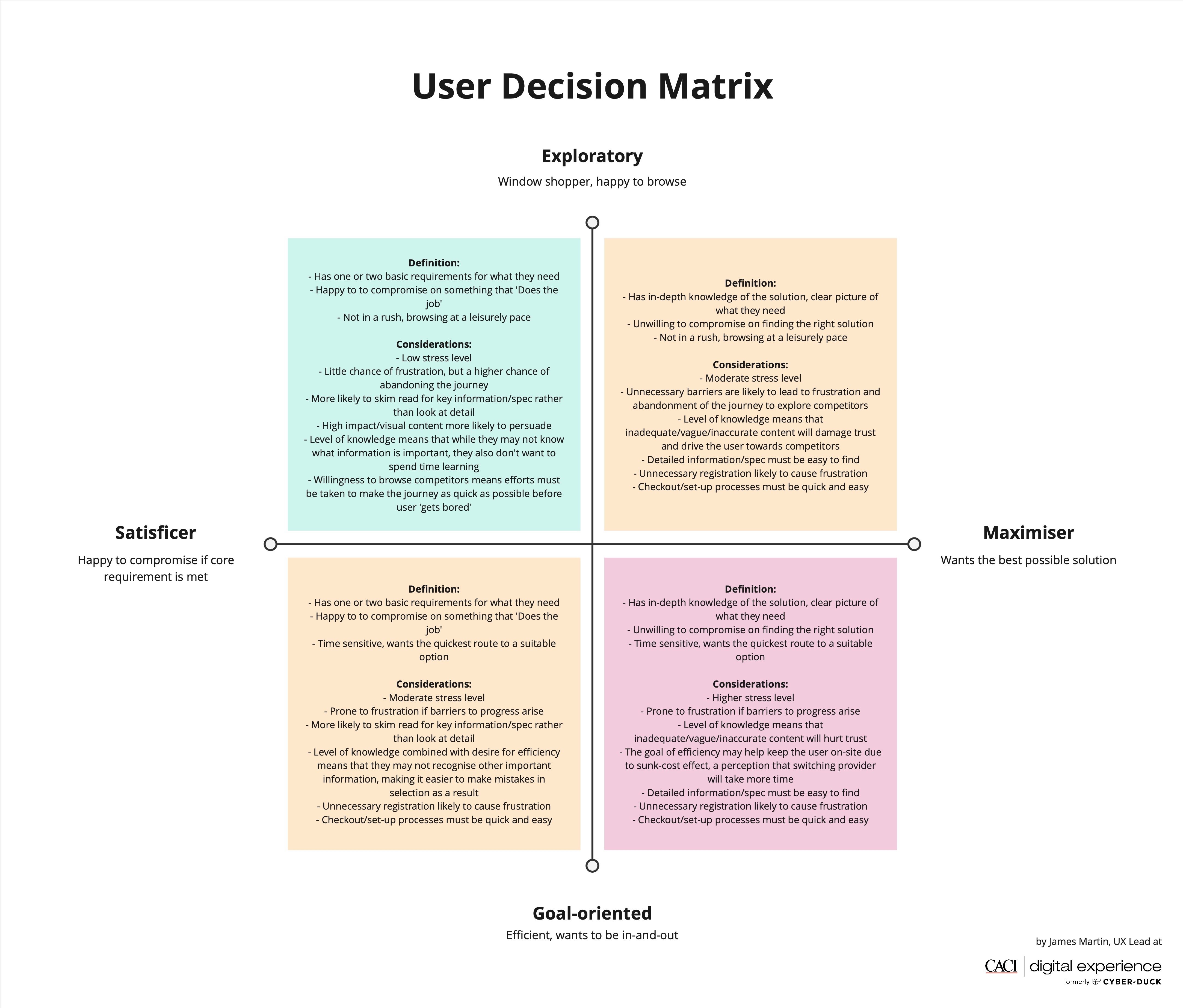

Allow me to introduce the User Decision Matrix, a tool that we use to define the requirements of different situations based on how our users will make a decision.

Within this matrix diagram you can see a variety of information. Firstly, the 4 key traits:

- Exploratory: Window shopper, happy to browse

- Goal-oriented: Efficient, wants to be in-and-out

- Maximiser: Wants the best possible solution

- Satisficer: Happy to compromise if core requirement is met

We then break down further into what this type of decision maker looks like under the ‘definition’. We also delve deeper into ‘considerations’ to get how a situation should be catered to depending on which quadrant it falls into.

Now that we are focusing on the broader context of our user’s situation, we can go beyond the surface level and start to tailor our whole approach to this user’s experience.

One persona type would find themselves in different quadrants based on the decision at hand. For example: we would find our ‘Mum, 35’ in the bottom left quadrant during the situation we previously described (opening a savings account for her child) - a goal-oriented satisficer. From this we can surmise that, though more information may be useful for other types of users, in this situation the user doesn’t necessarily wish to be educated. They don’t want to be experts; they prioritise efficiency and are perfectly happy with something that is ‘good enough’. We may decide that the user should have more information but that may push this user away in this event. There will of course be situations where ethically, we must highlight other information whether the user likes it or not. But there is a difference between preventing harm and choosing to overburden the user.

Now, what if this same user was looking for a mortgage? The stakes are far higher. There is more trepidation, more anxiety and fear over making the wrong choice. This means there's more care needed in this decision so this isn’t a time to settle, it is a time to browse. In this situation, we’re looking at an exploratory maximiser so it is important that we offer more information and support throughout the journey. We can bring in content that takes more time to digest and we need to ensure that we provide all the insight that the user needs to make this decision.

As you can see, this one persona has a radically different method of deciding based on the situation at hand. If we applied a general rule about what the user wants/needs in their various journeys based on the persona type rather than the situation, we may frustrate and alienate the user.

How do we create dynamic personas?

What does our process look like and how could you utilise the same approach?

- Conduct user research sessions: To facilitate the activities to follow, ensure a focus on cataloguing the different journeys and tasks that each research participant may seek to carry out. Equally, delve deeper to understand how they feel when making these types of decisions. From this you will create your basic persona types/groupings.

- Empathy mapping: Rather than diving deep into the static personas, take your types/groupings and create empathy maps. These place less focus on subjective assumptions about personality etc. As part of empathy mapping, you will list what the user ‘needs to do’.

- Tailor the User Decision Matrix: Adjust the ‘considerations’ within each quadrant of the matrix to suit your unique situations and user insights.

- Plot each need/journey onto the matrix: The aim is to use one matrix for either each user type or problem, depending on the research objectives. You will take the different tasks/journeys as detailed in your empathy maps and plot these into the User Decision Matrix. With this, we can see how one user will approach different decisions or we can compare how a range of different user groups will approach the same decision. (The difference in approach to the matrix will likely be defined by whether you are producing a range of personas as part of general discovery, or if you are looking into a specific feature or journey as part of the current work).

- Create tailored recommendations for each decision maker quadrant: The different quadrants that a need/journey features in will reveal the range of considerations and approaches that need to be addressed. This allows you to effectively craft your digital experience to suit each mental model for decision making that the journey requires.

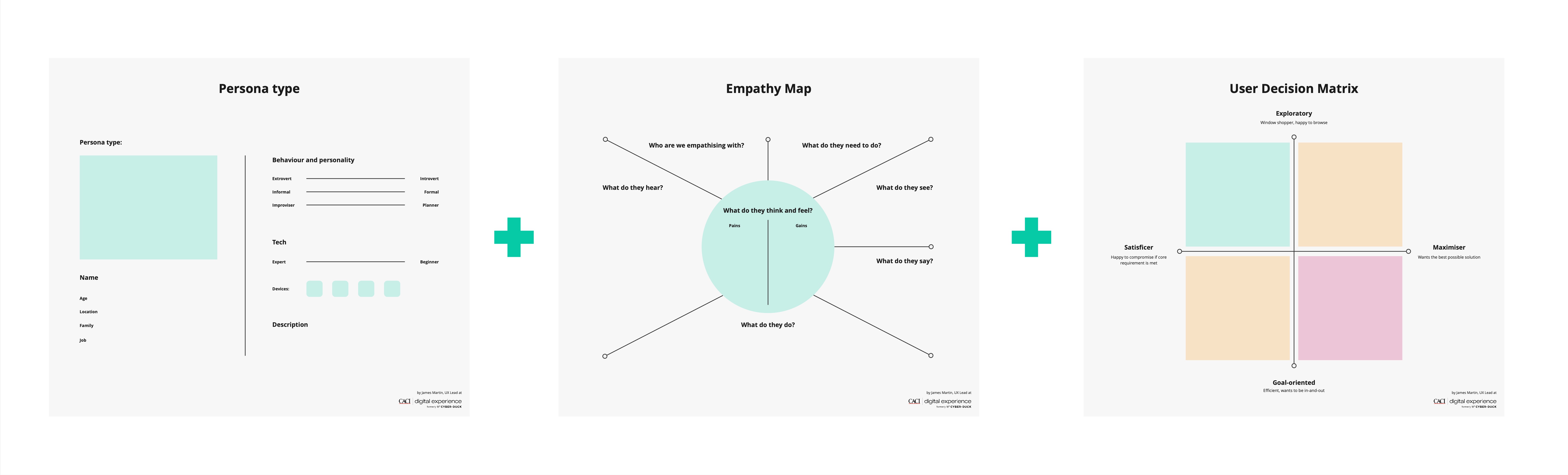

Our final dynamic personas ultimately consist of 3 key parts: the basic user type/persona card, empathy map and User Decision Matrix. The combination of all pieces not only describes the user, their thoughts, feelings, needs and pain points; but also, how their habits and behaviours will change when making different decisions.

Expanding the scope of traditional personas

In summary, dynamic personas allow us to expand the scope of traditional personas to also include specific insight into how different situations will impact on a user’s method of making a decision. Utilising a tool like the User Decision Matrix will help you catalogue the ways that different users will behave and make decisions in various situations. This assists us in creating journeys, content and interactions that lead to more meaningful digital experiences that satisfy the demands of the situation, the user and the organisation alike.

If you're interested in finding out more, take a look at our UX and design approach or contact us today and we'll see how we can help.